*********************This review contains mild spoilers*************************

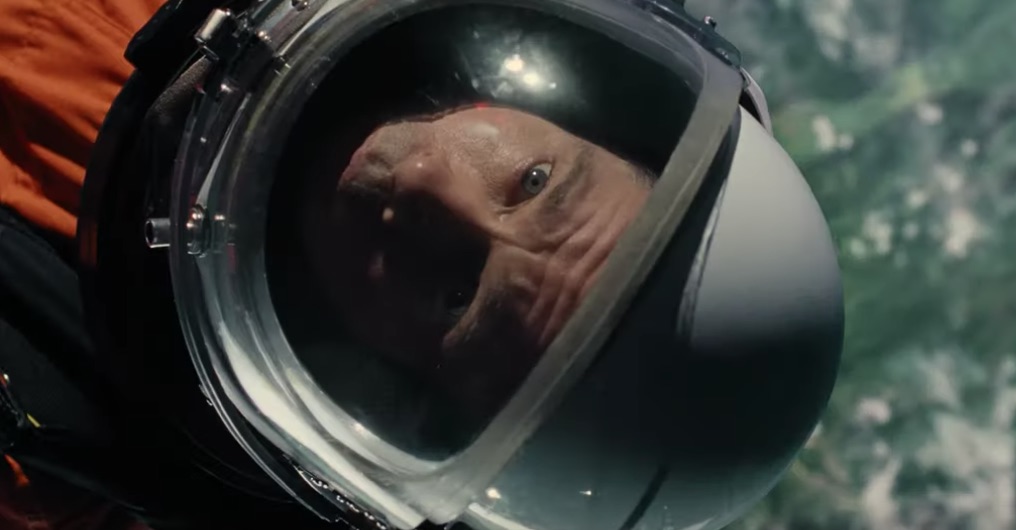

Some say that in order to accomplish great things, one must be driven to the point of obsession. You must have a one-track mind complete with tunnel vision that will not allow you to stop until you reach the summit of the mountain you are climbing. Having such an attitude will undoubtedly result in the achievement of some level of success in your chosen field, but what room will it leave for anything else? Such is the question we see explored in James Gray’s latest film Ad Astra starting Brad Pitt as Major Roy McBride in a distant future where he is sent on a mission to find and stop his father Clifford (Tommy Lee Jones), a pioneering astronaut sent to the outer Solar System near Neptune to search for life, from destroying Earth after a mutiny on his ship results in anti-matter power surges that threaten all life back home.

The plight of the McBrides calls into question the fine line between drive and obsession. Clifford is a legendary astronaut who decided to sacrifice his time and life toward searching for extraterrestrial life elsewhere. Nothing would stop him from achieving this, even the objections of his crew. In order to complete his life’s mission, Clifford kills the crew after they attempt to end the mission and return home after years in space with no progress toward a discovery. Similarly, after learning what his father really did, Roy stows away aboard the expedition sent to stop his father so that he may participate in their mission, inadvertently killing the entire crew in the process. Both father and son were resolute in their determination to complete their tasks at hand to the point where nothing would stand in their way, even other human lives. This line between being dedicated to something versus being detrimentally obsessed is one that has been explored through the stories of the world’s geniuses, from Steve Jobs to Marie Curie. Being driven toward something allows you to stay motivated to take risks and succeed. When drive begins to consume all else in your life, it crosses over toward an unhealthy obsession. Learning Clifford’s story and watching Roy’s unfold, we’re able to recognize this delicate distinction and understand what the tipping point may be. Drive allows you to integrate success into a life filled with great things, of which your passion is merely one. Obsession forces all good things to the wayside until you’re exiled with nothing and no one else beside you, as Cliff was. Striking an appropriate balance leaves one free to experience happiness and life in full.

While the existential question above is at the center of the film, Ad Astra also delves into the issue of generational curses and the weight of legacies. On Earth, Clifford is revered as an American hero, a classification that obviously effected Roy, as he followed that same professional path. Underneath this veneer of privilege however, was the negative effect that Clifford’s absence had on Roy as a child. Growing up without his father is shown to have clearly affected how Roy interacts with the world around him, particularly his ability to establish interpersonal relationships. The dedication to space that he inherits from Clifford has destroyed his marriage to Eve (Liv Tyler) who tired of his inability to connect. While Clifford’s status as space pioneer opened doors for Roy, it also saddled him with the generational curse of dogged dedication toward exploration that evolved into obsession and the loss of family.

This plot line has left a strong impression on audience members who see in Roy and Clifford’s story their own relationships with their fathers. Abandonment issues are a leading cause of anxiety and their effect on those who suffer from them can be long-lasting, as we see with Roy. But as real life studies have shown, and as we see in Ad Astra, overcoming the scars of broken relationships is achievable and the generational curse can be broken, if those affected face their underlying issues and come to terms with their past. Roy travels to the rings of Neptune to face the man responsible for his self destructive behaviors and lets go (literally and figuratively) of the trauma that held him back from becoming whole. What we witness play out onscreen is a good guide for how to deal with our own real life struggles and is undoubtedly behind the visceral reaction many are having to the film. So many of us, unfortunately, are carrying the scars of our pasts and the emptiness of lost opportunities with us everyday, much like Roy is. While we may not have the chance to directly confront the cause(s) as he did, confronting it even figuratively can result in the same closure and prospect of positive change that Roy attains by the film’s end.

Ad Astra features fantastic visual effects that bring space travel and fictional interplanetary bases alive and the wonder of space to the big screen. Accompanying the visuals are a grandiose, foreboding score from composer Max Richter that perfectly compliments the constant sense of dread present in many of the scenes. Brad Pitt gives a great performance as the spiritually broken Roy, beautifully communicating the hurt he lives with as a result of his upbringing. This fact makes it all the more curious that director James Gray chose to utilize so much narration in the film explaining Roy’s mental state, a lot of which was unneeded and slightly too explanatory. Still, the score, Brad’s performance, and the VFX may all receive awards recognition next year. Despite the many quality aspects of Ad Astra, the story does feel a bit like a carbon copy of past films we’ve already seen, namely Apocalypse Now, despite it being a good carbon copy. While a very good and worthwhile film, the lack of anything new to present keeps confined to the edge of the galaxy of very good and unable to make contact with the galaxy of great.

Image: 20th Century Fox